|

It's interesting to look at KSK as an upside-down fairy tale.

|

The tale opens narrated like a fairy tale, its frontispiece framed like the beginning of a storybook.

|

|

|

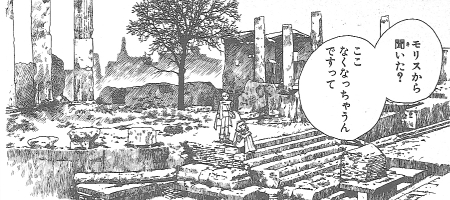

It even begins with a prince - so Funato said she designed young Ghaleon - but this is the tale of how the prince loses his kingdom. Fairy tales are usually about restoring a status quo - rescuing a blighted kingdom, or making the hero its monarch. This story argues that the blighted kingdom must be left in waste, to be reclaimed by strangers. |

|

It has a fairytale maiden, skilled in song; like Cinderella or Snow White, little birds gather at the window to watch her work. Her prince is never coming, though (at least, not the prince she wants), and she meets a wretched end. (This in a fairy tale would be a gateway to another trope, the parental figure whose death must be avenged; here, the tragic death is acknowledged as sadly unavoidable.) |

|

| There are would-be romances, but neither sees a happily ever after. |  |

|

There are no villains. The conflict is caused by inner demons and in facing an inevitable reality. The climax comes not through conquering, not through a knight slaying an evil king, but through understanding. The act of violence in the confrontation is not exhilarating but funereal. |  |

The tale ends on a bright and cheery note - but all three of those who receive a supposed fairytale ending have experienced great personal loss in the course of the tale, and underneath it all lies the shadow of how nothing will last forever - not even the protagonist's newfound peace with the world, as those who've played the game will know. Look ahead to TnK, and you witness the great achievement smashed to bits. You see the beginning and the end. Everything dies. There is literally no "happily ever after."

If Dain is a weird Lunar hero, then "Kokuhaku Suru Kioku" is a weird Lunar story. One could note that, in many of the above aspects, KSK also serves as an inversion of SSS, with two major additional points of rebuke. First, the big confrontation is between two women, something unthinkable in SSS, which seems intent on reducing its women to helpless or ineffectual damsels. Second, and more pertinent to the ideas at hand, is its more realistic treatment of its teenage protagonist, who is still a child and is not being set up to get the princess and the cool armor and become the bestest swordsman ever within the space of a few weeks. No one thinks,  understandably, that a 17-year-old can pull off a huge project like the construction of an airship, and Ghaleon has to undergo considerable training and lobbying to get anything off the ground. The protagonist is not omnipotent, and much of the start of the project is spent earning the confidence of others and getting help instead of going on a Kamehameha lone-wolf power trip. As opposed to the superhuman feats and boundless, near-effortless achievement of his game-hero brethren, Ghaleon's tale concerns itself with human (well, elven) frailty and the hard road to surmounting the external and internal obstacles in his path. understandably, that a 17-year-old can pull off a huge project like the construction of an airship, and Ghaleon has to undergo considerable training and lobbying to get anything off the ground. The protagonist is not omnipotent, and much of the start of the project is spent earning the confidence of others and getting help instead of going on a Kamehameha lone-wolf power trip. As opposed to the superhuman feats and boundless, near-effortless achievement of his game-hero brethren, Ghaleon's tale concerns itself with human (well, elven) frailty and the hard road to surmounting the external and internal obstacles in his path.

The key difference here is that while most fairy tales, the romances in which Lunar's heroes traditionally operate, are about wish fulfillment - about gaining - KSK's major theme is one of loss. The theme is most potently illustrated through the unique development of its central relationship: though Ghaleon ultimately finds his brother in one sense, he has still lost him in the tangible one. The acknowledgment he ultimately receives from Zain is never direct. The very beginning of the tale, Zain's funeral, is itself a closure, a statement that their relationship is over and can never be repaired; Ghaleon will never enjoy a loving living relationship with his brother. Ghaleon gains freedom and a better perspective on the world, yes, but (like Morris and Tagak) he must relinquish his home and family to do so. The story knows that most learning experiences work by taking something away rather than by giving you everything you want.

The nature of an inverted story with having an element and yet not having it, or also having its opposite, perhaps mirrors the strange limbo or double-role in which the protagonist finds himself - functioning as a child and an adult in the story at once, a younger member of a dying elder race; angry both at an absent parental figure and at the younger upstarts taking his people's place. The story's theme itself is explored along similar lines: the death of Funato's elves and their culture is certain, and yet they will live on through their impact on others. As the sun sets in one place, it rises elsewhere; though the young (as represented from a franchise-wide viewpoint by the SSS cast and their perspective on a changeover from elders to youth) and the old (as symbolized by KSK) view this situation from opposite sides of the looking glass, the same moral of moving forward and keeping one's eyes on tomorrow can be grasped from either angle.

The inversion of the fairy-tale archetype and its significance for the story and the larger world is perhaps crystallized by the main difference  between Funato's elves and their Tolkien inspiration. Tolkien refers to his elves' great vice as their desire to "embalm" the world, to preserve it from change. (This is known among real-world adults as the "everything was better when I was younger" syndrome.) Examine KSK's elven realm, though - there is no preservation from time. There is decay. Rot. Everything mazoku we see is flat run-down. Funato's elves may be creatures of magic, but even magic cannot hold back the march of time, and refusal to accept this fact results in not a beautiful ever-frozen living memory but in pervasive illness and ruin. between Funato's elves and their Tolkien inspiration. Tolkien refers to his elves' great vice as their desire to "embalm" the world, to preserve it from change. (This is known among real-world adults as the "everything was better when I was younger" syndrome.) Examine KSK's elven realm, though - there is no preservation from time. There is decay. Rot. Everything mazoku we see is flat run-down. Funato's elves may be creatures of magic, but even magic cannot hold back the march of time, and refusal to accept this fact results in not a beautiful ever-frozen living memory but in pervasive illness and ruin.

Back.

|